Take aways from the Civic Switchboard External Evaluator - Part 2

Final thoughts from our external evaluator Jake Cowan, an independent consultant who joined us in 2019 to provide insight to the impact of the Civic Switchboard project. See Part 1.

COVID-19 changed priorities or slowed progress of the work that 2019 field awardees intended to continue after their field projects concluded. Reasons for this included library closures, library staff prioritizing working on response and relief initiatives, and libraries facing resource constraints. In spite of this, most 2019 library field awardees are continuing to build relationships and initiate civic data projects. Only one of the nine original 2019 field awardees appears to be inactive in their civic data ecosystem a year after their project work. These were key findings from interviews conducted with 2019 field awardee team members that focused on their progress and activities one year after their Civic Switchboard work concluded. These interviews also revealed that some field awardees continued their Civic Switchboard field projects, and others have undertaken new civic data projects that emerged from the relationships they built during their work as Civic Switchboard grantees. Some examples of how these field projects continued and evolved include:

- Alaska: The impact of the pandemic was deeply felt in the state library. State resources were stretched thin by the pandemic, and oil revenues were also in decline. Their Civic Switchboard project has created sustaining value, however. There is variation in how the public can access data sets held by state agencies, because many state agencies are not fully resourced to publish and maintain data online and/or use different mechanisms for publishing their data. So the state library leaned into their mission to connect the public with state agencies, and they are planning a series of webcasts and/or tutorials with state agencies to present what data they have available and provide guidance on how to access and use it. The state library is planning these programs as a follow-up to their Civic Switchboard project and as a way to continue their participation in Alaska’s civic data ecosystem.

- Baltimore: This field project created an enduring partnership between the Bogomolny Library at the University of Baltimore, and the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (BNIA). Examples of how the library continues to work with BNIA include publishing step by step guidelines that allow university and community partners to make a link between library and civic data resources that are available on the library and BNIA web sites. The guidelines are promoted to faculty at meetings and conferences, and have been used in university courses.

- Western NY: In 2020 the Western New York Library Resources Council partnered with the City of Buffalo to host a virtual Open Data 101 workshop, and an Open Data Scavenger Hunt at a virtual library conference. They also hired an intern to create an Open Data Guide for Western New York. The Council is continuing to build partnerships and work on projects in their civic data ecosystem like these in order to grow more interest and buy-in from western New York libraries to take an interest in civic data projects.

2020 Field Projects – Initial Results

COVID-19 also changed the work of 2020 field awardees. They pivoted from work they proposed before the COVID-19 pandemic, and created new work plans for advancing their library and civic data partnerships that could be implemented virtually. There were a total of five field awardees in 2020; with one additional field awardee selected for funding but declining their grant award because they could not commit to the work they original proposed before the pandemic. Given this, a simple but important measure of success for these five field awardees is that they implemented projects. These were findings from interviews with 2020 field awardee teams focused on documenting key details and preliminary results from their work. Some early results from these projects include:

- Indianapolis Public Library created opportunities for library staff to understand the impact of COVID-19 in their services areas so that library services could be tailored and adapted to community needs, while also producing public events to help the public better understand the impact of COVID-19 locally.

- The School of Library and Information Sciences (SLIS) of North Carolina Central University and partners created a system for documenting the uses of racial covenants in real estate transactions in Durham, and through workshops created community conversations about the implications and legacy of these racist practices.

- Spokane Public Library positioned themselves as a key partner to the city for publishing open data and creating data governance policies.

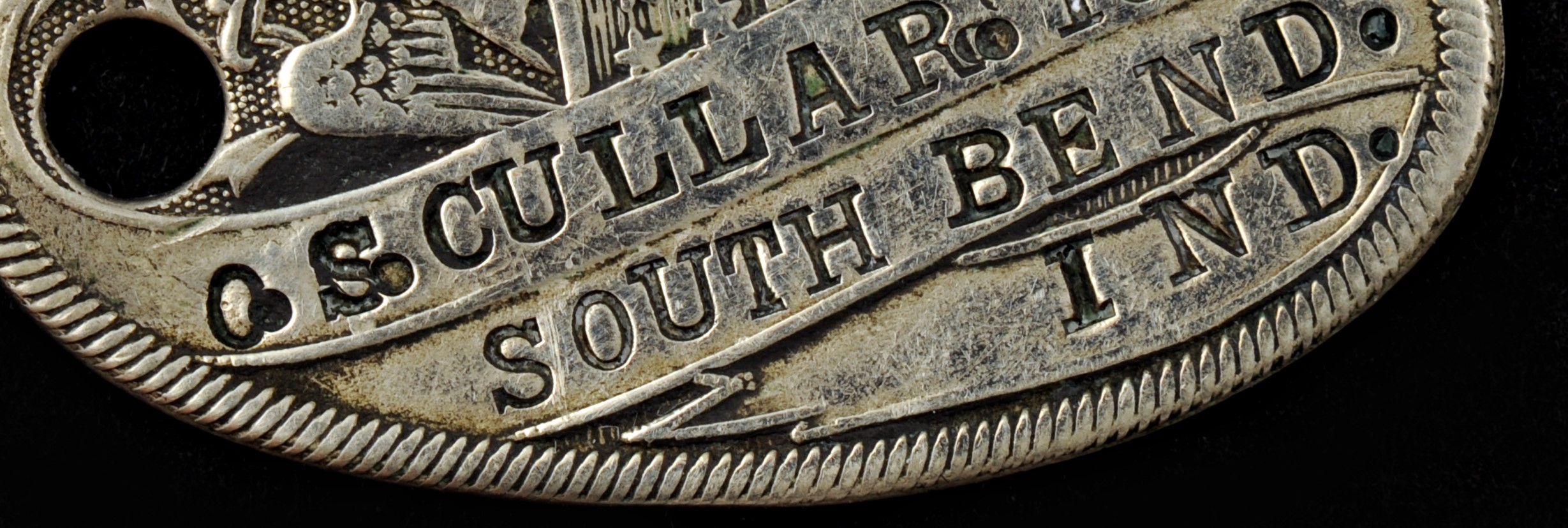

- St. Joseph County’s Public Library in South Bend gained key insights on the data literacy needs of the nonprofit sector, which will be used to guide programming in the library’s new Technology Resource Center.

- The University of Chicago Library convened key stakeholders that create and use criminal justice data to hear from people most impacted by the criminal justice system, and engage in a dialogue about policies that govern these data.

Across the experiences of 2019 and 2020 field awardees, libraries are deepening their roles in their civic data ecosystems. These libraries also demonstrate that getting started in civic data work can take time, and that the work is dynamic and changing. COVID-19 disruptions are the clearest example of how these libraries’ pathways into civic data work took time and underwent change. The work is also changing and dynamic because as libraries deepen their knowledge and relationships in civic data, they can better identify how best leverage the library’s roles and capacities to add value to the civic data ecosystem.

See Part 3.